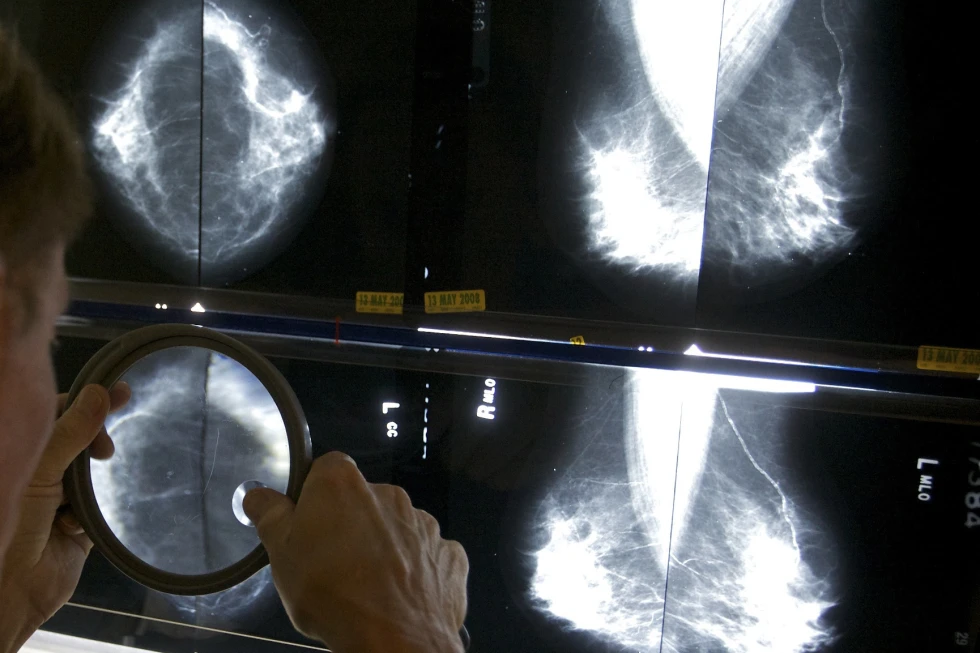

Annual mammograms have long been recommended for breast cancer survivors in many countries, including the United States.

The purpose of these yearly screenings is to monitor whether cancer has returned, providing peace of mind for patients and potentially catching any recurrence at an early stage.

However, a recent large-scale British study has challenged the necessity of annual mammograms, suggesting that less frequent screening may be just as effective.

The study, led by Janet Dunn of the University of Warwick and funded by the research arm of the U.K.’s National Health Service, sought to provide solid evidence for when women could potentially ease back on yearly mammograms.

The findings of the study have significant implications for breast cancer survivors and the healthcare system as a whole.

One of the primary arguments against annual mammograms is the anxiety and stress they can cause for patients. The constant fear of a cancer recurrence can take a toll on the mental and emotional well-being of survivors.

Additionally, the financial cost of yearly screenings cannot be overlooked. The expenses associated with frequent mammograms can be burdensome for both patients and healthcare providers.

Therefore, the potential for less frequent screenings to be just as effective is an appealing prospect for many.

The British study suggests that less frequent mammograms may be just as beneficial as yearly screenings for breast cancer survivors.

This finding challenges the long-standing recommendation for annual mammograms and has prompted a reevaluation of screening guidelines in the United Kingdom and beyond.

The implications of this study are significant and may lead to a shift in the standard of care for breast cancer survivors.

It is important to note that while the study provides compelling evidence for less frequent mammograms, further research and validation are needed to confirm these findings.

The potential impact on patient outcomes, healthcare costs, and overall quality of care must be carefully considered before any changes to screening guidelines are implemented.

In conclusion, the debate over the necessity of annual mammograms for breast cancer survivors is ongoing.

The recent British study has raised important questions about the frequency of screenings and their impact on patients and the healthcare system.

While the findings of the study are promising, it is crucial to approach any potential changes to screening guidelines with caution and thorough consideration of the potential implications.

As the medical community continues to evaluate and debate the best approach to post-treatment care for breast cancer survivors, it is essential to prioritize the well-being and long-term health of patients.

The findings of the study have significant implications for the current guidelines on mammogram screening for breast cancer survivors.

The results suggest that less frequent mammograms, such as every two years, are just as effective in detecting recurrence or new breast cancer in women aged 50 and older.

This challenges the traditional recommendation of annual mammograms for this population. The study provides evidence that less frequent screening does not compromise the detection of breast cancer, and may reduce unnecessary anxiety and medical interventions for survivors.

The implications of these findings are far-reaching, as they could potentially lead to a shift in current screening guidelines for this specific population.

Further research and consideration by healthcare professionals and policy makers are necessary to determine the appropriate screening schedule for breast cancer survivors aged 50 and older.

These findings highlight the importance of evidence-based medicine in guiding clinical practice and the need for ongoing evaluation of screening recommendations.

During the recent San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, Dunn emphasized the importance of providing women with the all-clear signal at an earlier stage, if possible.

The findings of the study, which has not yet undergone a full peer review, were presented and discussed at the symposium. The research involved over 5,200 women, all of whom were 50 years old or older and had previously undergone successful breast cancer surgery, primarily lumpectomies.

Following three years of annual screening, the participants were divided into two groups: one group received mammograms every year, while the other group received less frequent screenings.

This study sheds light on the potential benefits of less frequent mammograms for women who have already undergone successful breast cancer treatment, and the implications of these findings could have a significant impact on current breast cancer screening guidelines.

The results of this research will undoubtedly contribute to the ongoing debate on the optimal frequency of mammograms for women who have a history of breast cancer.

The findings of the study are indeed quite remarkable, with both groups showing similar results in terms of cancer-free survival rates.

The fact that 95% of both groups were still cancer free six years later is truly impressive and speaks to the effectiveness of the screening methods employed.

Additionally, the 98% breast cancer survival rate in both groups further emphasizes the significance of these findings.

Dr. Laura Esserman’s assertion that this study is “eye-opening” is quite telling, especially coming from a breast cancer specialist at the University of California, San Francisco.

Her statement indicates that the results of this study have the potential to challenge existing beliefs and practices within the medical community.

However, it is important to note that while the new study is indeed “very strong,” as stated by Corinne Leach of Moffitt Cancer Center, further research will be necessary to prompt any changes to U.S. guidelines.

Leach’s emphasis on the need for additional research in this area is a valid point, as guidelines are typically not altered based on a single study alone.

The fact that most women in both groups adhered to their assigned screening schedule is also noteworthy.

It demonstrates the willingness of participants to actively engage in their own healthcare, which is a positive sign for the potential implementation of any future changes to screening guidelines.

Overall, the findings of this study are certainly thought-provoking and have the potential to pave the way for further research and potential changes in screening guidelines.

It will be interesting to see how this study influences future research in the field and whether it ultimately leads to any shifts in current medical practices.

The recent findings regarding the less frequent mammogram schedule for survivors three years after surgery are indeed groundbreaking.

According to Dunn, survivors can now breathe easily as they resume a less frequent mammogram schedule, indicating a significant shift in post-surgery care.

This new approach is likely to have a substantial impact not only in the United Kingdom but also globally, as it is expected to change current practice and guidelines.

However, the frequency of these less frequent mammograms will vary depending on the type of surgery undergone by the survivors, as revealed in the study.

This development marks a significant advancement in post-surgery care and is poised to benefit survivors and healthcare providers alike.

In the less-frequent screening group, the protocol for women who had undergone mastectomies involved receiving a mammogram once every three years.

This approach was based on the understanding that the risk of developing breast cancer is significantly reduced following a mastectomy.

On the other hand, for women who had undergone lumpectomies, also known as breast conservation surgery, the recommended frequency for mammograms was every two years.

This was in recognition of the fact that while lumpectomy reduces the risk of breast cancer recurrence, regular monitoring through mammograms is still necessary to detect any potential signs of cancer at an early stage.

These differing intervals for mammogram screenings were established based on the specific medical considerations and risk factors associated with each type of surgery, aiming to provide optimal care and surveillance for women who have undergone these procedures.

The statement provided underscores the critical need for a more nuanced and personalized approach to breast cancer screening, particularly for those who have previously battled the disease.

The exclusion of younger breast cancer survivors from the study is a notable limitation, as their experiences often involve more aggressive forms of cancer.

This omission highlights a significant gap in our understanding of the specific needs and considerations for this demographic.

Furthermore, the assertion that women who have undergone double mastectomies do not require mammograms is a crucial point that challenges existing screening protocols.

This recommendation prompts a reevaluation of the current guidelines and emphasizes the necessity of tailoring screening practices to individual circumstances, including prior cancer history and treatment choices.

Dr. Laura Esserman’s call for a more personalized approach to screening is not only timely but also imperative.

It underscores the growing recognition within the medical community of the need to move beyond a one-size-fits-all approach to breast cancer screening.

The acknowledgment of the unique needs of breast cancer survivors, particularly in the context of screening, represents an important step towards comprehensive and patient-centered care.

In light of these insights, it is evident that a paradigm shift is necessary in the way we approach breast cancer screening.

Moving forward, there is a pressing need to develop and implement screening strategies that are tailored to the individual characteristics and histories of each patient.

This shift towards a more personalized approach has the potential to enhance the efficacy of screening efforts, improve patient outcomes, and ultimately contribute to a more comprehensive and empathetic model of care for those affected by breast cancer.

In conclusion, the observations made by Dr. Esserman serve as a poignant reminder of the importance of personalized care in the context of breast cancer screening.

It is imperative that we heed this call for a more tailored approach, ensuring that screening practices are not only inclusive of survivors but also sensitive to the unique challenges they face.

By doing so, we can strive to create a healthcare landscape that is truly responsive to the individual needs and experiences of those impacted by breast cancer.